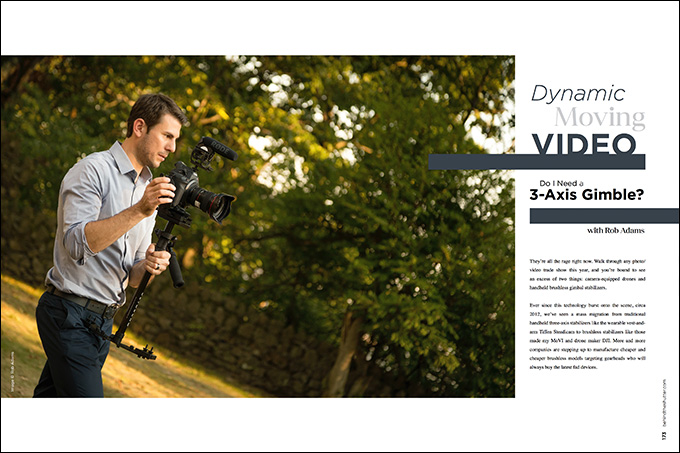

Dynamic Moving Video: Do I Need a 3-Axis Gimbal? with Rob Adams

They’re all the rage right now. Walk through any photo/video trade show this year, and you’re bound to see an excess of two things: camera-equipped drones and handheld brushless gimbal stabilizers.

Ever since this technology burst onto the scene, circa 2012, we’ve seen a mass migration from traditional handheld three-axis stabilizers like the wearable vest-and-arm Tiffen Steadicam to brushless stabilizers like those made my MoVI and drone maker DJI. More and more companies are stepping up to manufacture cheaper and cheaper brushless models targeting gearheads who will always buy the latest fad devices.

There are big differences between the two types of stabilizers, but the result (if utilized correctly) is essentially the same: a steady, floating camera shot that can instantly add production value to your motion images.

Cost-wise, you can find yourself breaking your budget for either type of stabilizer, depending on model and features. But I wanted to address the one factor that I see commonly overlooked while watching everyone jump on the brushless bandwagon: the use-case.

As a wedding cinematographer, portability and weight are two variables I’m always considering when adding new gear to my arsenal. In a stabilizer, I need something that can improve the steadiness of my shots but not produce other problems. I watched those awesome demonstration videos and drooled over the possibilities of creating jaw-dropping motion shots with the MoVI, but before dropping thousands on the newest gear, I wanted to take a hard look at each type of stabilizer and see which best fit my project and production logistics. Was it going to be the status quo, or was I about to own a new toy?

Steadicam and Glidecam: The Handheld and Wearable Camera Stabilizers

These two types of camera stabilizers have been the industry standard for the last 25 years. Most major television networks and broadcast outlets still use full-body wearable vest and arm combination Steadicam gimbal rigs to accommodate large television cameras that weigh upwards of 35 pounds. You see them commonly used during concert productions and live sporting events. There are no electronics involved, just good old-fashioned counterweights.

Wedding pros use these stabilizers as either a fully balanced counterweighted body-mounted rig or as a smaller, low-profile handheld sled-style stabilizer, which is perfect for small camera platforms like DSLRs and handheld camcorders.

The results, with proper training and practice, are stellar. The camera seems to float, and there’s a wide range of motion on all three axes, allowing for some pretty complex moves. Once an operator has mastered the balancing and muscle memory needed to create dynamic movements, a handheld Glidecam stabilizer, like the HD-4000 or the Glidecam Devin Graham Series, can produce fantastic results.

There are, of course, pros and cons. A full body-mounted rig like the Steadicam Zephyr or the Steadicam Scout can run upwards of $8,000 to $13,000 fully featured. They’re also not very portable. A large padded case is required to lug the stabilizer along on a shoot, and setup and breakdown can eat up valuable time if you’re a run-and-gun shooter like I am. Then, you need to be able to operate the rig smoothly and precisely. This takes training and practice.

The more portable option of this type of stabilizer is the handheld sled models produced by Glidecam Industries. These have been the wedding filmmaker’s go-to option ever since a cinema-style approach to weddings was made popular in the mid-2000s. They are lightweight, extremely portable (I’ve taken mine all over the world in just a small carry-on bag) and simple to set up. A few threaded twists, and it’s ready for a camera.

Learning to balance the Glidecam handheld sled takes some time, but once you understand how the counterweighted gimbal is positioned for your camera’s weight, including any accessories, it should take only a few minutes to lock in a dynamic balance. There are some great resources on YouTube on how to properly balance and use this stabilizer.

The downside here is that if you are using a slightly larger camera, like a Canon C100 or C300, RED Camera or similarly sized camcorder, you will find your arm getting tired quickly. For the amount of time that I use my Glidecam on a shoot, it is still a great option because I’m not operating it for extended periods of time or for capturing very long shots.

A big benefit of the sled-style stabilizer is the price. For less than $800, you can have a great stabilizer that produces amazingly smooth and level shots, and that has the ability to do complex movements in a controlled environment. It’s just a little limited if you are looking to perform more complicated movements.

3-Axis Brushless Electronic Gimbals

Brushless is a technical term for a type of motor that employs magnets to create motion; in this case, a counter-resistance force uses mechanical motors and precision electronics in a camera platform that is virtually immune to external motion and bodily interference. The active motors are always working to isolate the camera from external forces within set parameters and keep it level. It is the same technology that’s been used for years on helicopter-mounted camera turrets that allow for smooth but expensive sweeping aerial footage.

The technology has been miniaturized to work on a handlebar-style rig that you carry or mount to some other motion-controlled device. It’s hard to argue with results when seeing a well-balanced brushless gimbal used by a skilled operator. The possibility for complex motion shots is endless. You can sweep the camera from a worm’s-eye-view to an overhead shot with just a few steps—and some strong deltoids. I’ve seen these things passed back and forth through windows and between motorcycles cruising at 60 miles an hour, and the camera looks like it’s on a cable, weaving through and behind objects and actors. It’s a very cool method of getting dynamic motion shots. With their explosive growth in popularity and affordability, I’ve seen these handheld gimbals used on all sorts of productions, from music videos to weddings and fashion shows, even some reality TV shows.

One big thing I’ve noticed with this hot new trend is that you definitely get what you pay for. Going cheap on a brushless stabilizer is not a wise move. Some of the lower-cost models have not impressed me with the quality of the stabilization versus how heavy they are. A common misconception I see when filmmakers elect to go the three-axis brushless route is that they see how easy it can be to create smooth and versatile shots, but don’t understand that it still takes a tremendous amount of skill and sometimes even two operators to pull off such complex movements. Some models include a separate control mechanism for camera pan and tilt, requiring a second person to focus on the point of interest while the physical operator concentrates on the position of the camera within the scene.

While this can be an awesome benefit on a controlled shoot with a large crew and ample setup time, it’s not a great option for the run-and-gun shooter. Oddly, I see a lot of run-and-gun shooters try to adapt this method into their location shoots, only to be hampered by cumbersome setup and handling, with disappointing results. There are, however, proprietary and third-party camera control accessories that allow the camera’s tilt and pan movement to be controlled by a free thumb. (Some users have told me that they were never able to get proficient with a Glidecam or Steadicam, and that the brushless was easy to just pick up and use in a very basic straight-line manner. Fair enough.)

Among the distinct benefits of a brushless gimbal are its versatility in creating complex movements, multiuser functionality and the ability to mount it to a crane or jib for even more camera control.

But for me and my shooting requirements, the cons are a few too many. Balancing a three-axis gimbal takes time and patience. Many manufacturers market their brushless models as self-balancing; to a point, that’s true, provided you have the initial setup and camera placement correctly staged. On the models I’ve tested, the camera stays balanced after it’s set up, even if it’s turned off and on or set down. But if you have only one camera and it needs to be used in other ways during your shoot, you will find yourself balancing and rebalancing each time you remove the camera. The same goes for Glidecams and Steadicams, but I find it’s much easier to remove a camera from a counterweighted stage than a brushless cage.

Weight is also a major issue for me. If you’re using a small, mirrorless camera like a Sony a7Sii or Panasonic GH-4, a smaller brushless model like the DJI Ronin-M might be a good choice for manageability. But since I’m employing the Canon C100 on most of my jobs, I would need a larger model, such as the MoVI M5 or the DJI Ronin (larger model)—and the combined weight can get hard on the back muscles really quickly.

There’s also the issue of setting them down. You can’t just place a motorized brushless stabilizer on the ground to rest. It must be placed on a dedicated stand so as to not damage the delicate motors. This is a big issue for me since I’m always running around changing cameras and rigs during my wedding shoots. I would require a separate person just to follow me around with the support stand. I also find it difficult to adjust my camera’s settings while it’s mounted on a three-axis gimbal. Changing my exposure and focal length with a handheld sled stabilizer is simple due to the fact that I don’t have to support the whole rig with one hand while bringing the camera to eye level to see my settings. I’ve tried using an external monitor mounted to the top of the handlebar to make this easier, but that just added more weight to the whole rig.

For my wedding work, I’ve found that in order to keep on schedule, get the most from all of my devices and to stay light on my feet, a brushless gimbal just isn’t the way to go. I’ve been using a Glidecam three-axis handheld sled shooter for many years, and I still find that I can get amazing fly-shots that fit my style and client expectations wonderfully.

In fact, our drone uses a brushless gimbal that gives my film a unique perspective from the air, so I found the ground use of a gimbal to be unnecessary. I considered purchasing a brushless gimbal, and I really wanted it to fit into my workflow and be something that would bring my films to new heights. I had to ask myself: Will this purchase make me more money? The answer was no. The types of fly shots I can produce with my $850 Glidecam are exactly what I’d likely end up producing with a $4,000 brushless gimbal.

I use Glidecam Industries’ recently released Devin Graham Signature Series. It allows for easy, precise balancing via a telescopic center post that also allows me to fly low to get very close to the ground for some dynamic shooting. For the price and what it does, plus my extensive use of this type of stabilizer in the past, it’s the right tool for me. I’d certainly consider renting a brushless gimbal for a corporate or commercial film shoot that requires ultra-complex camera movement, but for now, I’m good.